When starting a new project, facing a blank canvas or a blank computer screen is daunting. Even after analyzing all of the project constraints, where is the starting point to synthesize the information and for create something from nothing? This is where literary devices, such as personification, analogy and metaphor, are useful tools to think about architectural design in the context of another medium such as literature, sculpture or, quite often, music (Goethe said ‘architecture is frozen music’).

Architects and all creative professionals use a variety of literary techniques to unleash their creativity and visualize problems in new ways. For example, a building’s relationship with its surroundings can be both literal like a slab on grade and metaphorical. A house may be a “tree” that climbs upward to tower over its site or a “boat” floating across the level ground. It may be embedded into the site like an earthen mass, or it may take a blossoming aspirational form that engages the sky.

A house as a tree (as opposed to a treehouse) may have roots in the ground, slender posts or columns and a raised canopy containing living space. There might be a sense of permeability at the ground allowing people to pass among its “trunks.” Occupied spaces are elevated, maybe due to a very steep terrain, and their scale is increasing complex recalling branches and leaves (allusion is another common literary device in the architect’s toolbox), as functional requirements of various spaces are met. The structure is most obviously wood, or maybe steel. It is probably not poured in place concrete.

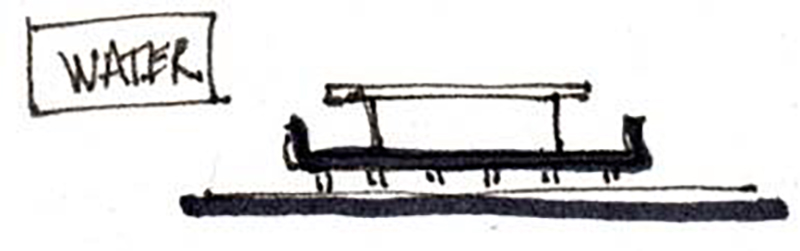

A house as water implies a broad horizon and flatness. It may be literally over water or just on a level ground plain, maybe in a flood plain. Large expanses of glass may evoke the transparency of water and shimmer in the low sun. It’s probably a single level as water does not stack very well. Mies Van der Roe’s Farnsworth house may come to mind.

Another meaning for the house as water may be fluidity. A modular house may accommodate a fluid design program by allowing easy additions and modifications. Or, this fluidity may be intended to capture the fungibility of water as in an organically shaped house that follows its terrain along the easiest path.

A house as earth feels like it should be heavily bermed or possibly embedded in a sloped site. Unlike the house as tree, the house as earth hunkers down and cuddles its occupants. We imagine this is due to a harsh environment like the Pueblo villages of the Southwest. Or, it may simply be a lack of building materials as was the case for early settlers in the American Midwest and countless examples of primitive mud and adobe structures. It can be both, of course.

The house as sky implies a structure open to the heavens that compels anyone looking at it to “look up.” A dramatic butterfly or other bold roof form may trigger this reflex. The roof is interesting less for its own shape and more for its silhouette. It engages with the sky, and the sky is an essential component of architecture. Looking upward also implies a sense of optimism and perhaps aspiration. Without articulating it as such, we often associate the exuberant architectural forms of mid-century design with a sense of optimism and spirit. When we engage with the sky, we must look up and look outward.

But the house as sky might also be a metaphor for a tower, ascending to the heavens. Metaphors can obviously allude to form as well as function and materials. If expanses of glass close to the ground are “water”, perhaps elevated glass or mirrored surfaces can be thought of as “sky.” The house of sky may feel ephemeral like a tensile structure.

In architectural design, the “why” informs the “how.” Metaphors are just a bridge (hah! another metaphor) joining the two. We use them to help guide our own thinking and our design choices in a consistent, or at least intentional, direction. They are also cultural reference markers for people less familiar with architecture to engage with buildings and understand them in their larger societal context (for example, the virtuous has as a “beacon on a hill”). Architects should think about their work in terms of metaphors but not be enslaved by them, even if these devices don’t directly influence design choices.

Metaphors are doors that help us let others into our design intent, and they are windows that can show us how others will see our design.