On a recent trip to Japan, where everything I saw was new to me, I was struck by the way old and new forms are used to express similar ideas in very different ways. At a simple level, a modern retaining wall along a roadside is canted and uses an interlocking pattern of herringbone block that recalls the battered walls of a 17th century Samurai castle. The materials and methods are different, but the practical purpose is the same.

Images: Retaining Wall – osap1111/Adobe Stock (top), Kanazawa Castle – David Marlatt (bottom)

The 16th century gate to Fushimi Inari Shrine in Kyoto and the 21st century gate by Ryuzo Shirae in front by of the Kanazawa train station, completed in 2005, each mark the passage from one state of being to another. At Fushimi Inari it is from the secular to the sacred. In Kanazawa it is from the transitory to destination. The Fushimi gate is an elaborate example of Miyadaiku woodworking while the Kanazawa gate references it and adds another metaphorical layer to its design with columns fashioned to reference the Tsuzumi, a traditional Japanese musical instrument.

Images: Fushimi Inari Shrine (top) & Kanazawa Train Station, (bottom) – David Marlatt

A wall separates spaces and marks a barrier and a border. Roughly ½ mile from each other but five centuries apart, long single-story walls fill similar functions, defining indoors and out. The minimalism and complete transparency of the facade of SANAA ‘s Museum of Contemporary Art is counterpoint to the opacity and heavy articulation of Kanazawa Castle. Kanazawa visually excludes outsiders by its heavy mass and opacity. It signals authority and hierarchy. SANAA’s curving glass museum wall signals inclusivity and rewards curiosity. While both walls are the same in offering limited controlled entry points, the SANAA wall feels permeable because of its transparency even though it is no more permeable than the stone and plaster castle walls. Each wall sends a message for its time. SANAA’s wall is democracy and transparency while Kanazawa is monarchy and opacity.

Images: SANAA Museum of Contemporary Art (top) & Kanazawa Castle (bottom) – David Marlatt

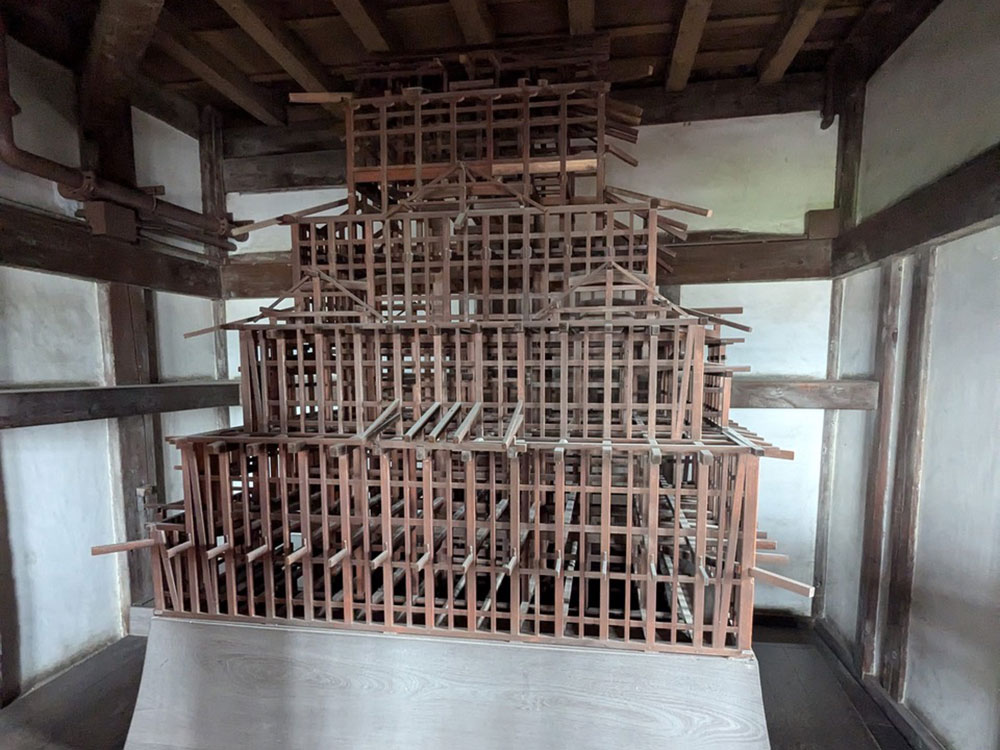

At first glance Noriko Horiuchi’s interactive sculpture, Net Forest, in Hakone’s Open Air Museum Park recalls a giant game of Jenga or pick-up sticks. It’s loose but intricate wood construction references Japanese joinery tradition. The timber framing visible in most shrines and temples, as well as a scale model of the 17th century Himeji Castle, created to guide complete reconstruction in the 1950’s, can be seen as symbolizing a multi-century tradition of assembling strength and stability through the sum of many parts. Net Forest recognizes those traditions without literally embracing them, leaving an opportunity for ambiguity and individual interpretation.

Images: Net Forest (top) & Himeji Castle Model (bottom) – David Marlatt

Large or small, windows are usually rectangular openings without many surprises. But unexpected shapes force us to think about their function, and ask ourselves, “why?” “what’s going on here?”.

The wall openings at 17th century Himeji Castle appear to be optimized for archers to defend the castle keep from attackers, but it is unclear why normally highly rational military design benefits from circles triangles and squares. Similarly, the 21st century Mikimoto building by Fumihiko Maki introduce ambiguity by jettisoning the traditional window to frame merchandise in new and interesting ways. Rather than understanding why these openings are shaped as they are, perhaps their intent is simply to provoke the question.

Images: Himeji Castle Wall Openings (top) & Mikimoto Building (bottom) – David Marlatt

Physically and metaphorically columns serve many purposes. Walking through just a fraction of the 10,000 Torii gates at the Fushimi Inari shrine in Kyoto is an immersive interactive rhythmic experience that hits you like walking through a symphony. The gates date from the 16th century but continue to be constructed even today. By contrast, in Kanazawa, just two columns precisely set against a reflecting pool at Yoshiro Taniguchi’s DT Suzuki Museum, completed in 2011, suggest the delicate rhythm of a water droplet or a pair of bamboo stalks, to be contemplated from multiple framed perspectives.

Images: Torii Gates (top) & DT Suziki Museum (bottom) – David Marlatt

The final entry into “architecture old and new” is not architecture at all. The Nijō Castle in Kyoto employed a brilliant intruder alert system called a “nightingale floor.” The nails in the hallway floor boards intentionally rub against metal clamps under the floor to produce a loud squeaking noise that immediately alerts the sleeping occupants of intruders. This is an obvious precursor to the motion activated security camera whose text alerts can awaken you at all hours.

Image: Nightingale Floor Detail, (top) & Modern Security Camera, (bottom) – David Marlatt